On 11 February, the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, the SECCA team looks at the current status and trends about women’s engagement in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in Central Asia, and how this links to the energy sector and energy transition in the Region.

In 2024, the European Union funded SECCA project undertook a series of national gender assessments in Central Asia, with a dedicated section investigating gender issues in the energy sector. The studies were presented and discussed during a regional conference that took place in Almaty (Kazakhstan) in October 2024. One of the topics investigated in this research included the distribution of girls and boys in fields of education related to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) as being the fields most directly related to and applicable in the energy sector.

In this conversation, SECCA Communications Expert Ms Nurgul Smagulova-Dulic and SECCA Gender Specialist Ms Silvia Sartori discuss the nexus of STEM and gender in the energy sector, in the light of this recent research.

Nurgul: What were some of the main findings from the studies you coordinated?

Silvia: The broader regional picture is quite aligned to international trends. First of all, we were confronted with a lack of accurate and updated gender-disaggregated data about the participation of boys and girls in STEM education. While the extent of this gap varied from country to country, it confirmed that, both globally and regionally, gender-disaggregated data are still not systematically captured, including in the different dimensions of the energy sector.

Secondly, the data that we were able to find indicate that, also in Central Asia, STEM studies remain predominantly male-dominated, to a different extent depending on the country and the quantity and accuracy of data available. In Kazakhstan, women account for up to 32 percent of STEM graduates. Similarly, in Kyrgyzstan, they account for 31.3 percent. For Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, we could not find any recent data. The latest we could find about Tajikistan, namely about secondary vocational education from the 2013-2014 academic year, that technical fields in Tajikistan are essentially pursued by men only. In 2014, Turkmenistan launched a new training programme on “Non-traditional and renewable energy sources”: one quarter of its graduates are women. Uzbekistan is particularly promising: according to the Statistics Agency, the percentage of women graduating from STEM programs in higher education is steadily increasing, growing from 32.6 percent in 2017 to 40.2 percent in 2021.

Nurgul: What are the reasons for this imbalance?

Silvia: In general, there is still little awareness about the importance of STEM, and the empowerment and employment potential that these sectors can offer. This is particularly the case when referring to the opportunities that STEM can provide to girls. The general perception is that these fields of study, and related career prospects, are not suitable for women. So, girls are discouraged from pursuing them from an early age.

In fact, we found not only that girls are under-represented in STEM. They are also over-represented in fields such as healthcare and education, which are associated with the roles traditionally allocated to women. In other words, the gender segregation in education mirrors and is a result of socially ingrained cultural norms around gender roles and aspiration: women are still predominantly perceived as key care-takers at the household level, whereas men are expected to be the household’s breadwinner.

As a result, many girls lack confidence in their abilities in STEM. This keeps them further away from the prospect of embracing an education, and then a career, in these sectors. It is a vicious cycle that perpetuates existing gender inequalities and risks to create new ones, as the labour market evolves in conjunction with the energy transition.

Nurgul: How does this impact on the employment patterns in the energy sector?

Silvia: We can say that education is the first window where gender imbalances in the energy sector become visible, and the gender gaps that start there go on to generate a cascade of other imbalances.

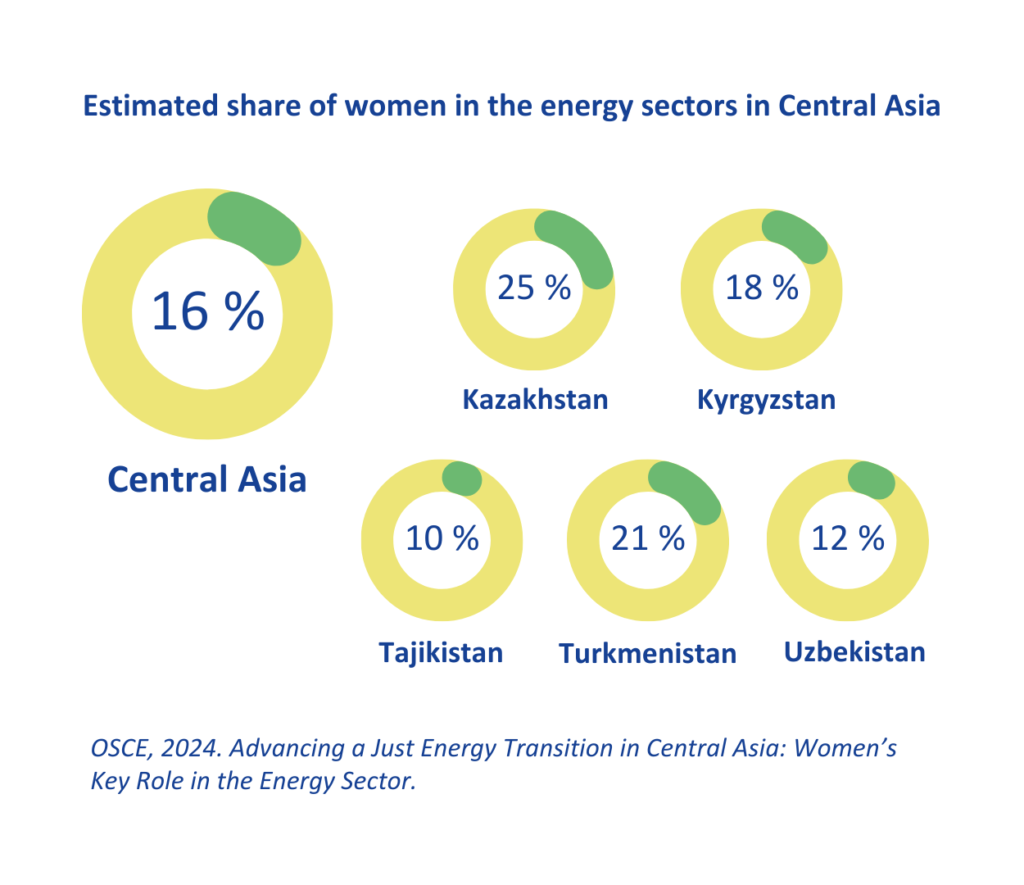

First of all, the share of women working in the energy sector in Central Asia is substantially lower than that of men: women account on average for 16 percent of the workforce in the energy field. In fact, the energy sector displays one of the highest gender imbalances in the workforce among all industries.

It is not only a quantitative problem but also a qualitative issue. Besides being significantly fewer than men, women working in energy companies are mostly employed in administrative positions, whereas higher managerial and leadership positions are occupied by men. In fact, women are confronted with several challenges, including the gender pay gap, not only to enter the energy sector but also to get promoted and advance their career in it.

Nurgul: Does this apply also to the clean energy segment?

Silvia: The renewable energy sector portrays a more nuanced picture: women’s employment therein is estimated to be higher than in the traditional energy sector in the cases of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. In Kazakhstan, renewable energy employs fewer women than the traditional energy sector, whereas no notable difference between the two sectors is reported in Turkmenistan, as far as women’s employment is concerned.

Nurgul: Which stakeholders can play a role to address these gaps?

Silvia: As with all gender issues, everyone has a role to play in advancing gender equality and promoting more inclusive societies. But there are specific stakeholder types that, according to our studies, are particularly well positioned to drive change here.

We found recurrent references to the role of parents, and family environments, in directing children and the youth in their selection of studies. More than on their interests, their skills and competences, young boys and girls in Central Asia decide what to study based on the recommendations, perceptions and expectations of their parents and adult family members. It is therefore very important to work closely with families, and parents in particular, to build their awareness about the opportunities that the STEM fields have to offer, to girls and boys alike.

Secondly, when looking at specific measures to attract girls to STEM, we found several international initiatives in Central Asian countries, such as “Girls in Science” or “Skills4Girls” by UNICEF or “STEM4ALL x Mentoring Her” by the UNDP. National stakeholders have so far focused on drawing the youth’s attention to STEM. While this is surely welcome and needed, additional and dedicated efforts are needed, at the national level, to increase the specific participation of girls in these fields. In Kazakhstan, for instance, Atyrau Oil & Gas University launched the first dedicated Executive MBA program on “Women’s Leadership in the Energy Industry”. Civil society also offers some promising examples: in Tajikistan, for instance, the NGO Jahoni Mo empowers women and girls through STEM, providing IT skills and knowledge to help them pursue successful careers in the field, and the NGO Shams supports schoolgirls from rural areas to pursue higher education in STEM.

Industry players also have a key role to play, and here as well we start seeing some promising examples. Increasing qualified female professionals in the sector is not only a gender justice principle, but also a business priority for the countries to be able to run and sustain their energy transition efforts. In the last few years, the Region witnessed the creation of several associations of women in energy, such as the “Women for the Just Transition Network” in Kazakhstan. In Uzbekistan, for instance, Uzbekenergo established a Gender Equality Board and the company “Thermal Power Plants” established a Women’s Council.

By scaling up and replicating at a wider level these promising measures, countries in the Region can benefit of a more inclusive and resilient development. And regional cooperation is another avenue that holds significant potential for stakeholders to join hands, exchange best practices and advance common priorities.