February 11 marks the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, which was launched by the UN General Assembly in 2015 to acknowledge, promote and celebrate the role of girls and women in science and technology.

SECCA Communications Expert Nurgul Smagulova-Dulic sits down with Gender Specialist Silvia Sartori to dig deeper behind the meaning and relevance of this International Day.

Nurgul: Why is this day important?

Silvia: This international day is important to shed light on the contributions by women to scientific advancement but also to promote their full and equal participation in what are known as STEM fields, that is to say science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Currently these fields are confronted with a significant underrepresentation of girls and women. UNESCO, which is one of the implementers of this International Day together with UN Women, reports that women account only for 33.3% of global researchers.[1]

These imbalances reflect a larger, underlying gap between girls and boys, women and men in access to resources and assets, including education, and contributes to perpetuating existing inequalities.

That is why international days such as February 11 are not just important – they are necessary to draw attention to gender inequalities and to prompt action to address them from all angles.

Nurgul: What causes this female underrepresentation in STEM? And why does it matter?

Silvia: This gap starts very early, from cultural values and social expectations that discourage girls to embrace careers traditionally considered as “masculine”. This imbalance becomes visible at school already: according to UNICEF, 18% of girls in tertiary education are pursuing STEM studies, compared to 35% of boys. And if the number of boys and girls studying natural sciences is similar, girls are significantly lagging behind in engineering, manufacturing and construction.[2]

Other reasons include financial constraints, lack of female role models, unconscious bias in the learning environment or lack of gender-sensitive training and curricula. In the workplace, women are subject to discrimination and biases as well as limited mentorship and support networks.

The gender imbalance in STEM is crucial, in many respects. In terms of social justice, it deprives girls and women of equal opportunities. In research and employment, it deprives the STEM sectors of the talents, skills and potential contributions from women. And this is all the more critical given the scale and relevance of the current global challenges we are confronted with, from climate change and decarbonisation to health emergencies, as we have recently experienced with COVID19.

Relying on a wide, innovative and diverse workforce is essential to manage these processes. It is also a business necessity, if we are to address significant talent shortages that are already visible in many sectors and regions.

Nurgul: Does this issue affect Europe, too?

Silvia: Female underrepresentation in STEM is a global problem. In Europe female researchers and engineers accounted for 41% of those employed in science and engineering in 2020. And only 19% of the workforce in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in 2021 was made of women.[3]

There are significant differences from country to country as well as nationally within each country. In 2020, for instance, Lithuania, Portugal and Denmark had a 52% share of female researchers and engineers compared to about 30% in Finland and Hungary.[4]

Nurgul: What approaches have been tested in Europe to address and try to reverse this trend?

Silvia: To encourage more female enrolment and employment in STEM studies and jobs, several initiatives have been launched, at different levels and by different stakeholders.

An example is the EU-funded “The Girls Go Circular Project”, which is equipping 40,000 schoolgirls aged 14-19 across Europe with digital and entrepreneurial skills by 2027. Through an online learning programme about the circular economy, it supports girls developing their own solutions to societal and environmental challenges. The project also organises every year the “Women and Girls in STEM Forum”.

At the national level, there are initiatives such as the Spanish programme “Mujeres con Ciencia” (“Women with Science”) which supports the participation of women in scientific research by providing funding for research projects, training, and networking opportunities.

Civil society and private sector are also active in promoting wider engagement of girls in ICT and STEM. There is for instance the “HKUnicorn Squad” in Estonia, a privately funded, girls-only technology hobby group movement that gathers girls in lower secondary schools and tries to reduce their “fear of technology”, increase their interest in technology and robotics, and scientifically measures if a “girls only” approach generates different impacts compared to mixed classes.

Nurgul: What is the situation of girls and women in STEM in Central Asia?

Silvia: Girls and women in Central Asia are affected by the same types of challenges described above, including gender stereotypes, lack of role models, cultural barriers and employment discrimination. Additionally, for those who live in remote or rural areas, access to quality education, including in STEM, is further out of reach. The share of women in STEM fields in the region varies by country and by area within STEM.

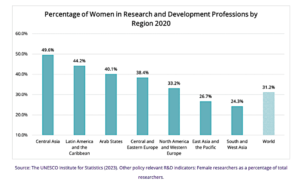

Nevertheless, UNESCO data indicate that Central Asia boasts the highest ratio, globally, of female researchers. With a 49,6% rate, in 2020 the region almost approached gender equality, and was almost 20 percentage points ahead of the world average. It is noteworthy that in 2022 women accounted for 54% of Kazakhstan’s researchers![5]

Also, when looking at some specific fields, such as female graduates in energy disciplines, recent figures from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are similar to those from France, Germany and the USA.[6]

On the other hand, it is difficult to draw a picture on the status of Central Asian women’s employment in STEM fields, in terms of both the share of women employed and of the type of positions they hold. Many countries in the region do not regularly collect and publish gender-disaggregated data on STEM employment, nor do they necessarily share the same definition of “STEM” fields. This affects the collection and comparability of data. Estimates suggest that Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan have the highest share of women employed in STEM in the region.

Nurgul: How does this relate to the work of the SECCA project?

Silvia: The project mainstreams gender equality throughout its activities in support of the transition towards sustainable energy in Central Asia. For instance, we always strive to ensure the collection of gender-disaggregated data and proactively try to engage women professionals as trainers or speakers in the activities we organise. The project also holds dedicated activities to enhance gender equality and women’s empowerment in the energy field. We are currently compiling Gender Assessments in the region to analyse the relation between gender and sustainable energy.

References:

[1] UNESCO, International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/days/women-girls-science

[2] UNICEF, Mapping gender equality in STEM from school to work. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/mapping-gender-equality-stem-school-work

[3] EIT, Women and Girls in STEM Forum. Available at: https://eit-girlsgocircular.eu/wgsf23-robot-challenge/

[4] Eurostat, More women join science and engineering ranks. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20220211-2

[5] EL KZ, Half of Kazakhstan’s researchers are women. Available at: https://el.kz/en/half-of-kazakhstans-researchers-are-women_56221/

[6] OSCE, Advancing a Just Energy Transition in Central Asia: Women’s Key Role in the Energy Sector. Available at: https://www.osce.org/oceea/561811

This publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the consortium led by Stantec and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.