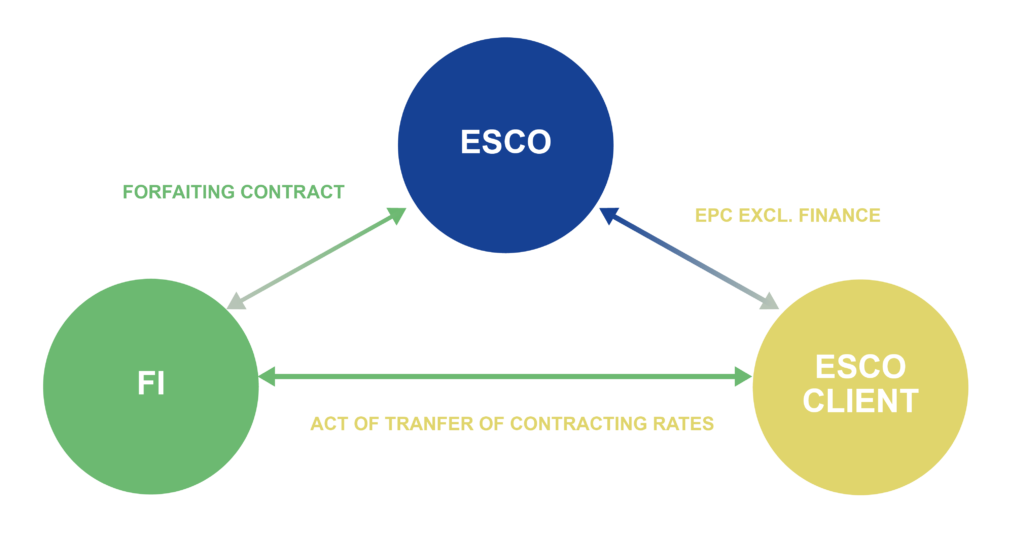

Forfaiting

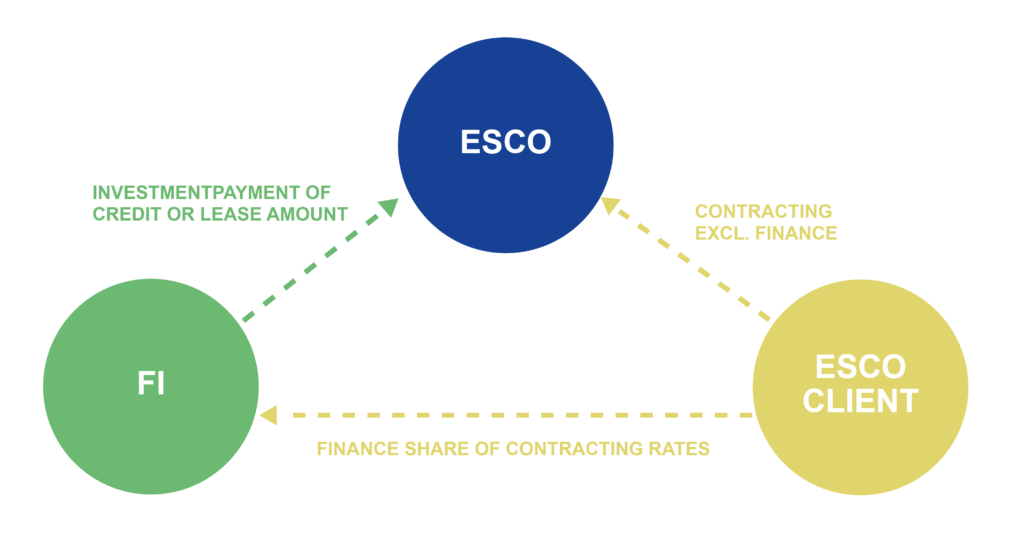

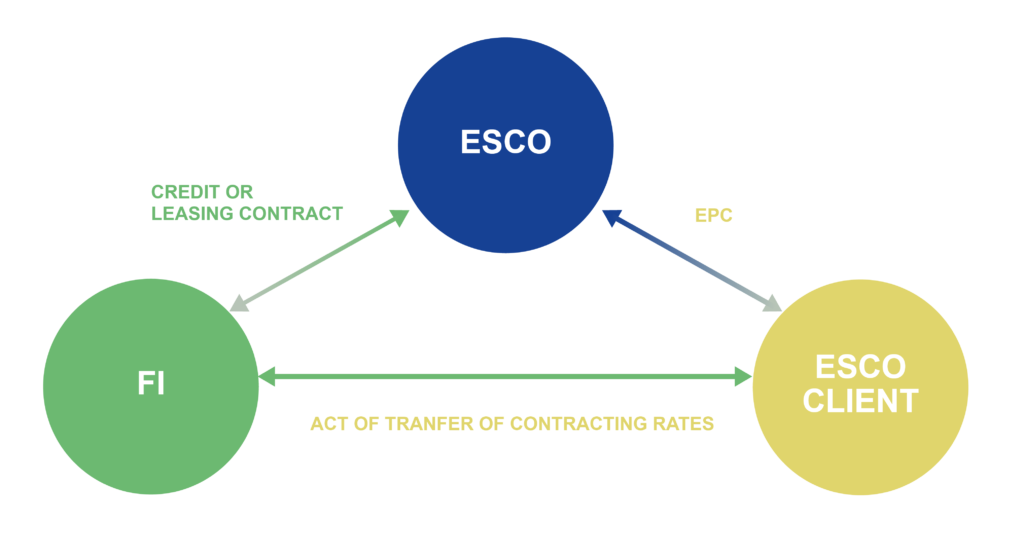

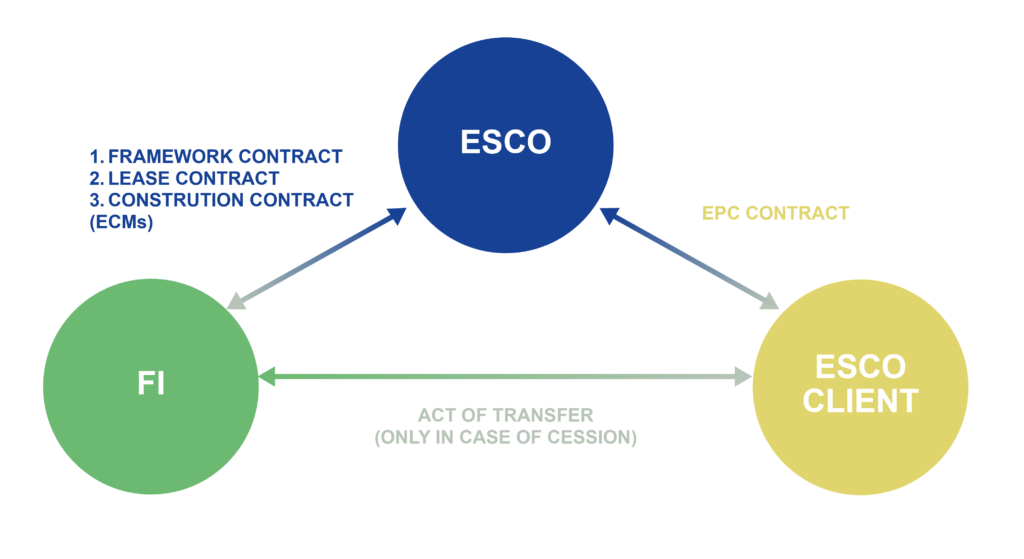

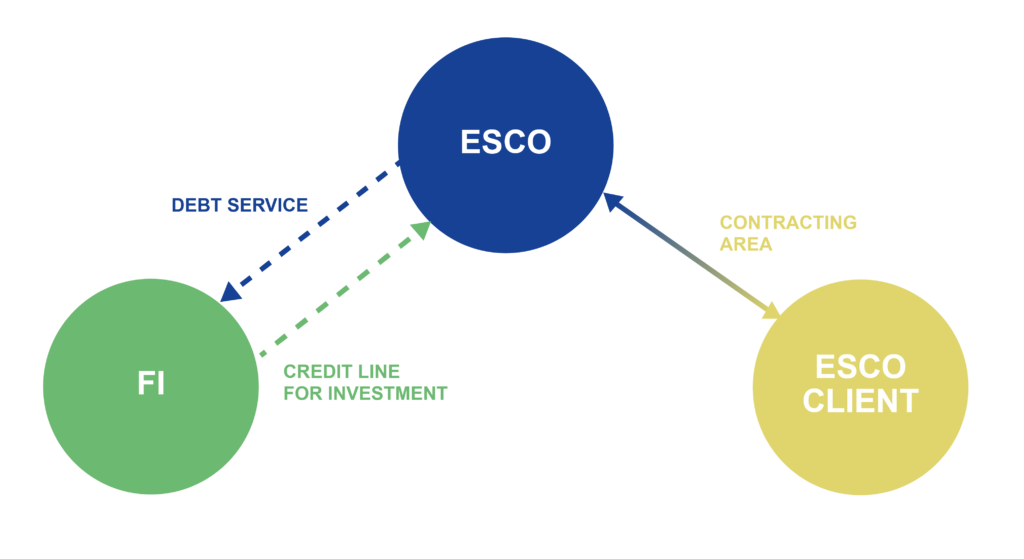

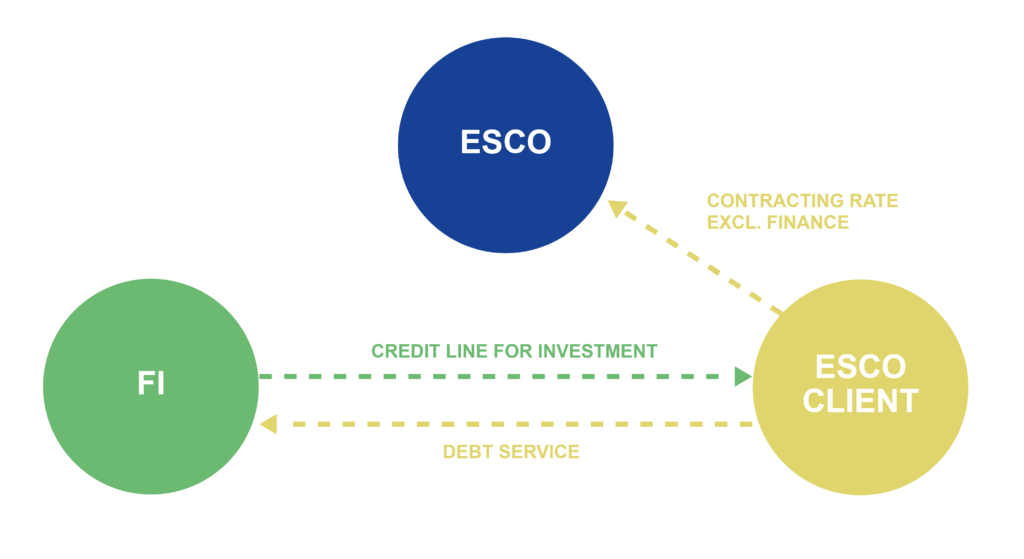

Forfaiting contracting, in its purest form, involves the ESCO transferring the rights to future receivables – specifically, the payments expected from an energy performance contract—to a financial institution (FI). In exchange for this transfer, the ESCO receives a single lump-sum payment, which is discounted to account for the time value of money and the risk associated with the receivables. This arrangement does not require the ESCO to enter into an additional financing agreement, as the financial institution assumes the risk of collecting future payments. The structure of the contractual relationships involved in a forfaiting transaction is typically represented in a diagram that illustrates the flow of payments and the transfer of receivables.

ESCO Client, ESCO and FI usually sign a “Notice and Acknowledgment of Assignment”. The ESCO Client acknowledges herein the continued payment obligations to the FI regardless of any disputes between ESCO Client and ESCO. A hidden cession without an assignment between all partners is also possible within this model but is not common.

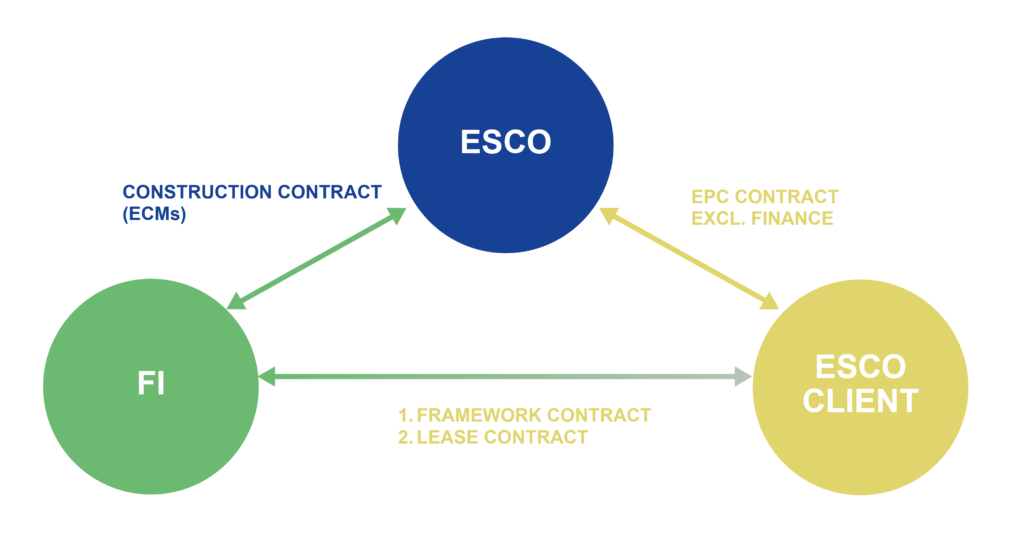

The most important precondition is that the receivables are legal, rightful and undisputed. Based on successfully implemented ECMs & RE, the ESCO Client must confirm the performance by different quality securing instruments so that the ceded share of the contracting rate is legally rightful. Additionally, the ceded receivables must be undisputed, meaning that the payment of the ceded contracting rates must be settled independently from the further performance of the ESCO regarding O&M and/or EPC-guarantees. These preconditions can be met through the following models:

- Energy Supply Contracting (ESC) with ceding of the Basic Service price of the rate

- EPC with ceding of the fixed/accepted part of the rate or

- EPC with ceding of the total contracting rate in combination with a penalty or a bank guarantee in the case of insufficient performance of the ESCO

The integration of a bonus-malus system as an incentive for the performance of the ESCO is possible within all three models.

As mentioned before, the amount forfeited should be limited to the financing share of the contracting rate. A sensible limit could be the investment plus capital cost share of the contracting rate. The remaining share (for O&M, energy supply, risks …) is paid to the ESCO separately over the contract term.

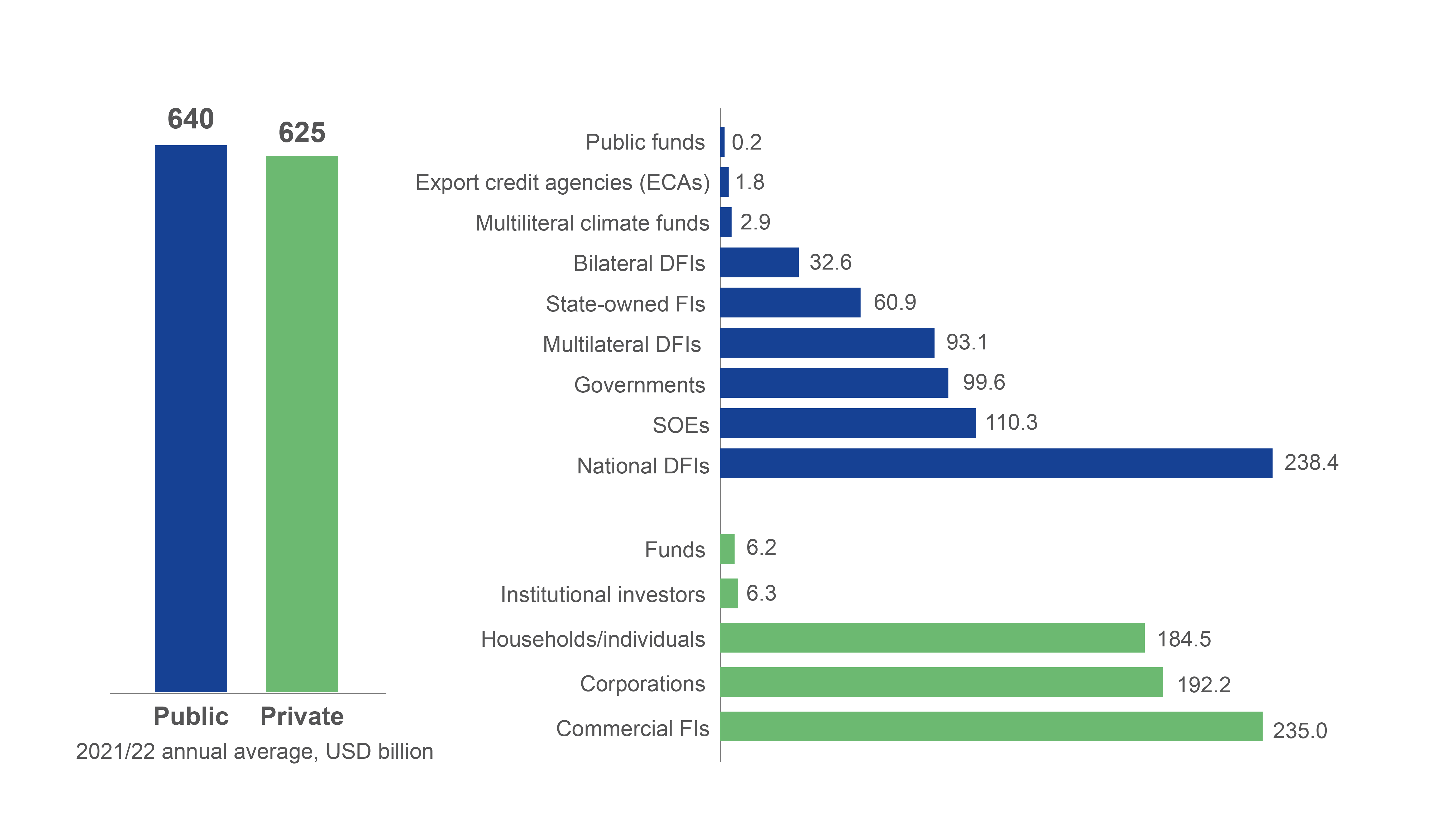

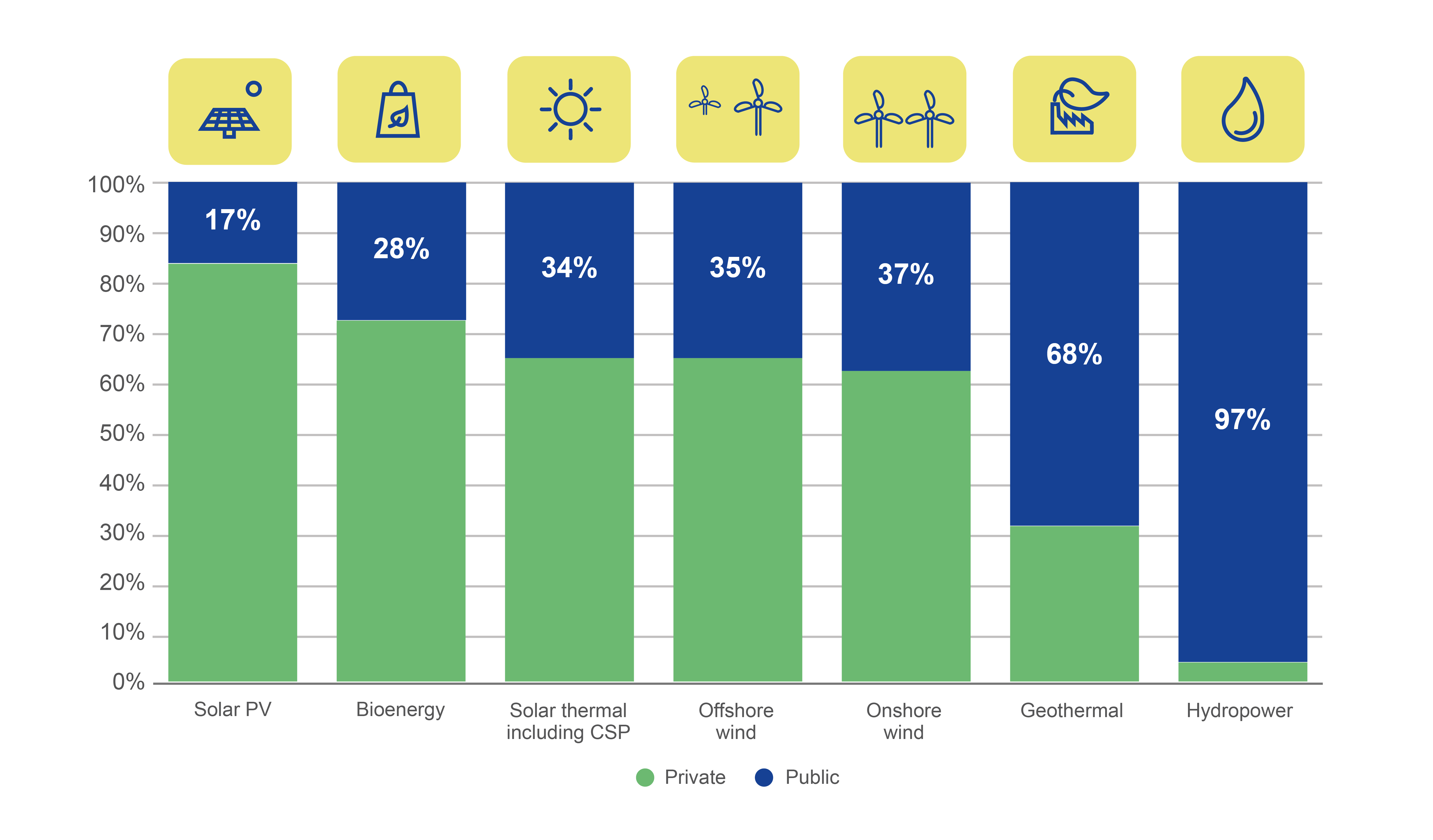

Source: Climate Policy Initiative

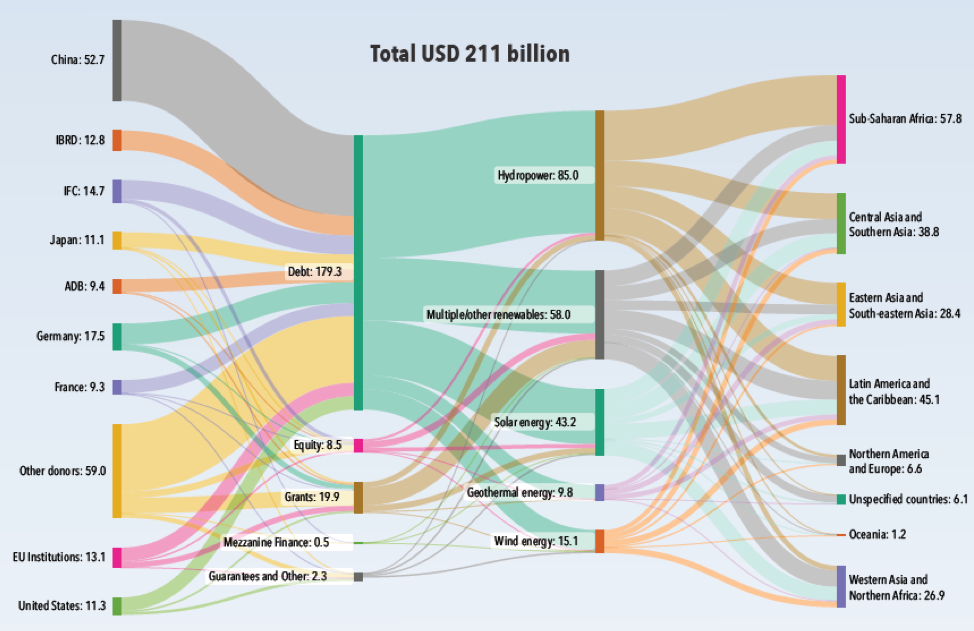

Source: Climate Policy Initiative Source: IRENA

Source: IRENA